- Home

- Opal Edgar

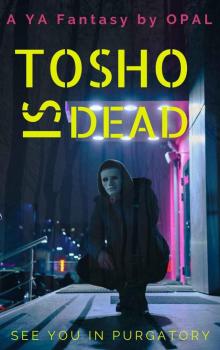

Tosho is Dead

Tosho is Dead Read online

TOSHO IS DEAD

Book 1

To my brother

The question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love?

—Martin Luther King Jr.

Chapter 0

Voices in My Head

Berlin, 26th May 1961

The story started the night I began to hear the voice. I was 16.

“Hey! Show your face you Nazi pig!”

Not that voice. That was just Andreas behind me. We had gone to school together, another lifetime ago. Before I got brutally kicked into the workforce ranks. I stopped walking.

The streets were empty corridors of ruined buildings and crumbling walls. They had been left untouched since the end of World War II.

I turned.

The last sunrays highlighted Andreas between two fire-licked pillars.

“Sorry, you got the wrong guy.” I forced my face into a smile.

“ We’re tired of you and your degenerate family’s Aryan mugs polluting our city. So you’re going to follow all the signposts back to your fascist rat hole.”

My smile dropped a notch. When we lost the war, the Soviet Union marched into the country. My mother, towing my baby self, ran for her life, leaving everything behind. The land our family had owned for generations now belonged to Polish farmers. We were the losers: we deserved having everything taken from us. Now, my mother and I shared a one bedroom flat with my aunt Maud, her peg leg and my two cousins in East Berlin.

Andreas was a bully, but I wasn’t his usual target. I stood a good head taller than him and had gained ten kilos of muscles in the last six months. They had started building up when I began ploughing away on the construction site. I hung onto the last threads of calm I had.

“And abandon my patriotic duty? I’m helping rebuild this beautiful Berlin you love so much, comrade. You need me ’cause all the other men are dead, just saying.”

“You think you’re funny?” raged Andreas.

I thought about it for a second and finally measured one centimetre between my thumb and index finger. It was true, though. The war had devoured a whole generation of men. We were so desperate for workers that we imported them by the truckload.

“It’s a bloody wall of shame you’re building us! Numbskull!” Andreas yelled, growing redder in the face by the second.

And maybe he was right. The work crew had started pulling down wrecks and good houses alike in a great line. People weren’t meant to know about it, but who were the politicians trying to fool? The allies were sure a fascist rampart was the only way to stop the leftover Nazis from invading the good, and proper, Europe.

“Well, I loved chatting and all …” I waved goodbye and walked off, like I should have from the very first word.

A tall copy of Andreas stepped out from the shadows. His elder brother was almost my height with bangs of flat, chestnut hair running across his pink face. His girlfriend was sweet Ada, who’d given me more flowers than I’d paid for last week. It had been my mother’s birthday. But Johan was the very personification of jealousy.

“You’re not getting off that easy.” He punctuated this with an uppercut.

I heaved and staggered backwards. I had to get out of here before it turned ugly.

“Aryan-boy. Papa’s boy—”

My blood ran cold. My fists closed in white knuckle crunches and my dumb, so very dumb, smile had a stroke and died.

“—you’re a copy of him, right? Popped streight from your little Nazi mold.”

Anger took over.

“My father’s in hell where he belongs.” And my fist crushed into his face, shutting him up. Johan collapsed. His neck fell squarely into the crook of my elbow. Blood pounded in my ears. I dragged him back up and rammed his back into the ruins of the old bank. Rocks showered down on us – surprisingly accurate in their aim. A big one hit me on the head. The world blinked out for a second.

I swayed. And remembered to breathe, gulping dusty air frantically. At the end of my arm Johan’s head lulled over the bullet-hole-pitted wall. For a second, it looked like a firing squad kill zone. I heaved again, feeling sick to my stomach.

I wasn’t my father.

I let go and stepped backwards, staggering, shaking the anger out of my arms. I wasn’t my father. I looked at those blue lines running under my skin. It hurt knowing his blood coursed through my veins. But I hadn’t chosen who my parents were. I wasn’t any worse than anyone round me. I really wasn’t!

Was I?

A crimson drop splattered on the asphalt. Whose was that? Pain radiated where the rock had hit. I ran my fingers through my hair. Grazing the wound sent an excruciating wave rushing through my body. My hand came back bloody. My legs turned to water.

What are you doing? Don’t let go. Why did you let go? You had him!

That was the voice. The voice that changed everything. Male, educated, butter-smooth and sure of itself.

On the ground, Johan was relearning how to breathe. He couldn’t have said that. And Andreas sounded too squeaky for it. Who was egging me on?

“Show yourself!” I yelled, nausea still gripping me.

I scrutinised the cracks and holes in this bombed memorial to the shame we carried.

You can’t be talking to me, the voice said.

“I hear you!” I yelled again.

I squinted at the buildings in the darkening light. I’d heard the voice as clear as if he stood next to me.

Oh, you have no idea how fantastic that is, Tosho. It laughed.

“Do I know you?”

A hand came out from a window where the glass was long gone. It gripped a flier. On it: a blond-haired, ice-blue-eyed family looked to the horizon. Father and sons proudly wore army greens, and all of them smiled in front of a flapping swastika. It was easy to recognise the propaganda calling youth, clones of myself, to join the SS forces. Was the kid, with skinny arms and dirty cheeks, calling for all hell to break loose?

“Nazi pig!” he screeched.

He wasn’t the voice. Other hands came out of different windows, and heads appeared from round every corner. This was an ambush.

See what you get for being soft? You should have finished him.

None of their lips had moved. I counted 11 heads. That meant 22 hands and just as many feet. My army of four limbs fell awfully short.

“Wow, a whole crowd hating me,” I said, turning to the dirty-cheeked screecher. “What did I do to you?”

His answer was a slingshot. Bigger hands held tightly rolled up newspapers. They might have looked innocent enough, but I’d seen them before: bent paper clubs strong enough to break bones.

“You know, the Americans proved big blond Aryans are dumber than any other human on Earth.” Andreas spat on my shoe.

“And now we’ll make you leave, Aryan-SS-boy,” Johan added.

“You’re just scared Ada will see you for what you truly are if she gets the chance to compare you to a real man. I might have pig-killer blood in me, but at least I don’t have the face of one.”

It was the voice! And it came out of my throat.

For a second, all the boys held their breath as the words hung in the air. But then someone exhaled, and Johan leaped at my throat. We rolled in the dirt. A shower of projectile flew over us. In one smooth movement, the boys reloaded their slingshots while Andreas and the bigger kids kicked my ribs in. The thumps of their leather soles rattled the world.

Good work, the smug voice said.

“Hey!” someone called. “Git off him, vermin!”

Their words were deep and heavily tinted by an Eastern-European accent. The boys scattered faster than rats.

That bunch of brats almost offed you, the voice said, almost

cheerful.

The heavy footsteps of Turkish workmen rumbled closer. For a second, I lay under a blanket of purple and orange sky. The next second, Seden had his hands on my face. His thick black hair fell over his frown. We were the same age. We’d met at the construction site. He had come with his father a few months ago when Germany has signed the contract with Turkey. Since then, the workers had kept pouring in. They had no prospects in their own country, he’d told me. I smiled at Sedan. We understood each other. We both dreamt about building a better future, but instead we were just given enough concrete to mould a prison round ourselves.

“Tosho, you not looking good.”

Behind Seden were many of my workmates. They wore worried eyes topped by worried eyebrows.

“Can you walk?” Seden asked.

“I guess,” I said.

His father slipped his arm under mine and we headed towards the death strip. Between ourselves, that is what we called the long road of flattened houses.

“Allah bless me. I see the day when racist white men kill each other!” Seden laughed.

My ribs hurt too much to join in. The walk felt longer than it ever had. We went right through the construction site. The death strip stretched for kilometres: an open wound on the face of the city. We didn’t stop before reaching West Berlin. Here the city gleamed new and clean under perfect streetlights. The wrecks had been pulled down and replaced. Only when I arrived at the guest workers’ dilapidated housing district did I feel at home.

A large expanse of ground outside was layered with cardboard so people could sit anywhere without dirtying their trousers. The sky was our ceiling and the stars sparkled like Christmas candles. It was unusually hot: the workmen had set enough fires ablaze on the broken pavement to warm our hearts. They’d taken over the street for Eid-al-Adha and had invited me along.

I didn’t know much about Eid, except that it was an important celebration which stopped my friends from eating during the day. Now that night had fallen, exotic scents of spiced stews and grilled meats drifted from every corner.

Seden and his dad sat me on cushions piled in a corner of their shack – they were ready to be taken outside. A blue eye-bobble hung above my head on a nail keeping the window permanently shut. It was about the size of my palm: flat and translucent like glass.

“Maybe you need it better than us,” Sedan mocked. “The Nazar boncuğu eye keep evil away. Or maybe you don’t ... You still have all your teeth.”

I grinned.

“Thanks, but if my face looks as bad as it feels, I’m in trouble.”

“Ah yes, women trouble.” Sedan sighed before laughing. “You not keep Ada’s love very long with a face like that.”

“Just ’cause she smiles at me they all go imagining stuff!” I exclaimed.

“You handsome like actor. And scars give character. But that hole in the head is not good.”

He poked into my hair and I winced. Could there be broken bones in there?

“It’s not as if that skull of mine protected anything precious,” I said through clenched teeth so as not to yelp in pain.

“Stop stupid act,” Sedan answered. “We put your head back.”

“I hope you have a load of superglue to do that – like real soldiers.”

“No American glue. Better than glue. We have honey baklava!”

Sedan’s father came back with a pile of neatly folded clothes, worn but clean. He placed them next to me and crouched by my side.

Someone brought me a plate of food and an improvised band played ballades like nothing I knew.

It’s getting late, isn’t it? I’m bored.

I jumped, startled at the thought. I liked it here! But it came from the voice. I sat straighter on my cushions and swore as my head swam. Sedan blinked. He’d been miles away too. All round me men spoke in Turkish and laughed. I didn’t understand any of it, but the chicken rice soothed my stomach. By the time I got up, I almost felt like I could walk all the way home without help.

“See ya!” Sedan called out as I waddled away to the death strip.

“Elveda!” I called back. “Did I say it right?”

“Perfect! We’ll make a real Turk of ya!”

The feast disappeared as I turned my back to the fires. Grey buildings loomed in the dark, closing over me. I staggered along the way like a drunk man. There had been no alcohol at the party, Muslims don’t drink, but I sure wished I’d been given something to lessen the pain. Home was far, on the other side of the death strip.

“Going somewhere?”

A silhouette shuffled away from a wall. He wore a cloak and his face was hidden in the shadow of his hood. A trick of the light from a window made his eyes flash red.

“Come on, Andreas, that’s enough for today. You won,” I said.

“Goodbye, Tosho.”

He stepped closer. Andreas looked tall.

“Johan?” I asked, still unable to see his face.

A sharp pain in my back drove me to my knees. I tried to turn. No muscles answered. I opened my mouth, but only a gurgling sound came out.

The world tipped on its side. I was on the ground. Damn it, I hoped I hadn’t ripped Sedan’s shirt. I couldn’t breathe. Bubbles were in the way. I shook. I was so cold. Then everything went black.

Chapter 1

Waking up With a Headache

My head hurt. My arms too. And my legs, bones and everything really. Ideas hurt.

Finally, princess, welcome to the party! that damn voice said.

My eyes flew open.

Artificial lights pierced them like needles. I threw my arm up for protection. Tears ran down my face. I blinked them away trying to make out what was round me.

The light flowed down from a ceiling carved out of pure sunrays. It warmed my skin like summer heat, and basked everything in glitter. It would have been heavenly if it wasn’t for the ground.

I was in a corridor crammed like a candy store junkyard. To get to the other wall you had to climb over furniture, wreaths of flowers and gaudy knick-knacks. In some places the rubbish reached as high as the ceiling, partially disappearing into the misty light. I could move only by scooting sideways along the wall and tucking my stomach in.

I discovered new muscles I had no idea I had. They pulled like crazy round the bruising— I bit my tongue as a hard lump hit me square in the back.

And that’s a strike! Doorknob: one, Tosho: zero. The voice laughed.

“Shut up!” I yelled.

The door banged closed. Damn it! I’d just frightened my way out. I turned round. The handle rattled under my hands, but the simple plank door would not budge.

“Please open. Please. I’m lost,” I said.

A click resounded from within. Now that was just cruel. I hadn’t even seen who was on the other side. There was no windows anywhere to look in, or out. There was just the junk and doors on both sides of the corridor as far as my eyes could see. Not one door was the same. They ranged from crazy blood-red iron portcullis, to lace curtains over a concrete slab, to a solid Maya gold gate. How big was this place?

Note to myself: be careful of the doorknobs. Not only were they all a different design, but they all reached a different height. The common factor was how much they hurt when rammed into your ribcage.

I rattled the knob more frantically. And then, under my very eyes, the cold porcelain handle unravelled like a ball of yarn. I grabbed at it, my hands struggling against the panic-struck knob, but it spun away and looked like it was being sucked into the door. I tried to readjust my grip, tighten it and hold on, but the doorknob was diminishing faster than I could keep up. In seconds, it had become a mere thread. It wiggled out of my grasp and wormed itself into the door, leaving behind a smooth surface with nothing to hold on to.

My arms fell down my sides in shock. I backed as far away as I could from the door, which was about a quarter of a step. Then I was stopped by a carved beam.

Where was I?

You’re in the shadow corr

idor. You’re dead. Now, chop-chop, you’ve got an appointment to attend, the voice echoed in my mind.

I shook my head, trying to dislodge him out of my right ear. Slapping the back of my head hurt. So I stopped. I was going insane. I had to get a grip on myself. Maybe I could ignore him. Maybe there was a rational explanation for all of this. Maybe there was an underground landfill in the city. Maybe Andreas dumped me after the beating: literally abandoned me in a dump. After all, why should the surface of Berlin be worse than the underground?

I looked up. It was so bright. That had to be a semi-opaque tarp to protect this place from the open sky. So up was the exit.

I flexed my arms and rubbed my neck: hoping to loosen the burning knots of my frayed nerves. I could do this.

The voice laughed. Oh this is precious!

“Stop it,” I mumbled between clenched teeth.

I looked on both sides of the corridor. I was utterly alone. I crab walked to the closest table and displaced the Asian comb and dagger there, so I could climb up. I stepped over a cat statue and rolled straw mats. I took a deep breath, this was not going to be fun. With a leap I reached a staircase carved from a single tree trunk. My whole body throbbed. Luckily, it was easy to hike to the top. I reached the misty ceiling and pushed my arm up.

The bright fog engulfed my hand. No tarp. I lost sight of my fingers. Perplexed, I pushed further and— Thud.

I hadn’t expected hard plaster. No. The texture and temperature were wrong. Cold polished stone was more like it. But how could it glow like that? I pushed harder, hands flat on the ceiling.

Yeah, do that. Don’t give up: this is hilarious! the voice said.

Suddenly, the ceiling lost its density. It grew fuzzy and my fingers slipped through. It must have been glass, not stone. I had found the skylight and pushed it open. At least that’s what it felt like. Not being able to see anything made the guesswork frustrating. I searched for a ledge, any corner or frame to hold onto, but the whole roof had opened up. I went up on my tiptoes and moved my arms back and forth, left and right, ignoring the pain. What was going on?

Tosho is Dead

Tosho is Dead